+ A warming Arctic is ushering in increased development across the region, exposing new infrastructure and populations to uncertain operational risks and dangerous hazards.

+ Arctic nations’ search and rescue (SAR) capabilities vary widely, and none are sufficiently-equipped to meet the needs of commercial operators when emergencies inevitably arise in this rapidly-developing region.

+ The Arctic Council’s Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement does not establish a minimum SAR capability threshold for any of its signatories, making gaps and inconsistencies challenging to overcome.

+ There are steps the Arctic Council can take to improve the Arctic SAR Agreement, namely chartering a committee with regular meetings and exercises and developing a common operating procedure (SAR COP) database for registering all national, local, and private SAR assets available to support regional operators.

Arctic development implies increased presence. As the region becomes more accessible, Arctic and non-Arctic nations have their eyes on development activities in the Northern Frontier. Member nations of the Arctic Council recognize this and are driven to guide the inevitable development in a responsible and sustainable fashion. This development will involve significant new infrastructure. Both permanent and transient populations will increase rapidly. The coming years will see workers, shipping personnel, and passengers aboard recreational vessels flock to the Arctic region during the warmer months.

Eventually, either due to medical emergencies or major calamities, members of this increased Arctic population will need to be rescued.

Companies hoping to capitalize on the warming Arctic will be doing so in an environment of uncertain risk. Organizations operating in the Arctic environment need to plan for the potential rescue of their own people with ill-defined state assistance. The Arctic Council should revisit and refine the Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement in order to increase the commitment of Arctic Nations to search and rescue efforts and to reduce uncertainty for organizations wishing to operate in the high northern latitudes.

The Dire Condition of Arctic Search and Rescue

Extreme weather conditions and sheer distances involved in polar region operations present challenges more difficult for rescue personnel than are found in any other region on Earth.

Preparedness to conduct SAR is not equal among the parties to the Arctic SAR Agreement. Norway has considerable permanently stationed air and sea assets along the majority of their periphery. Additionally, a 2017 RAND study that was focused on SAR capabilities in the Alaska region found that the US Air Force and Coast Guard are “fairly well postured” for Arctic SAR operations.

"The uneven distribution of SAR assets, lack of infrastructure, and absence of a multinational common operating picture present a major obstacle to sustainable Arctic development: uncertainty."

In contrast, the Canadian Report of the Standing Committee on National Defence: A Secure and Sovereign Arctic painted a dire picture of Canada’s SAR capabilities. The report highlighted the deteriorated state of Canadian Arctic infrastructure and emphasized the challenges Canadian SAR assets have in responding to events in the far north of Canada.

The SAR picture near Greenland is even more grim. Airstrip and port infrastructure anywhere other than the south of Greenland is either completely absent or significantly deteriorated since construction. The US maintains Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base) in northern Greenland but with no permanently stationed SAR personnel or equipment.

The uneven distribution of SAR assets, lack of infrastructure, and absence of a multinational common operating picture present a major obstacle to sustainable Arctic development: uncertainty. Uncertainty makes government organizations, commercial developers, and professionals in the leisure and shipping industries unable to sufficiently measure or mitigate the risks of operations in the Arctic region.

An Extraordinary First Step, With Limitations

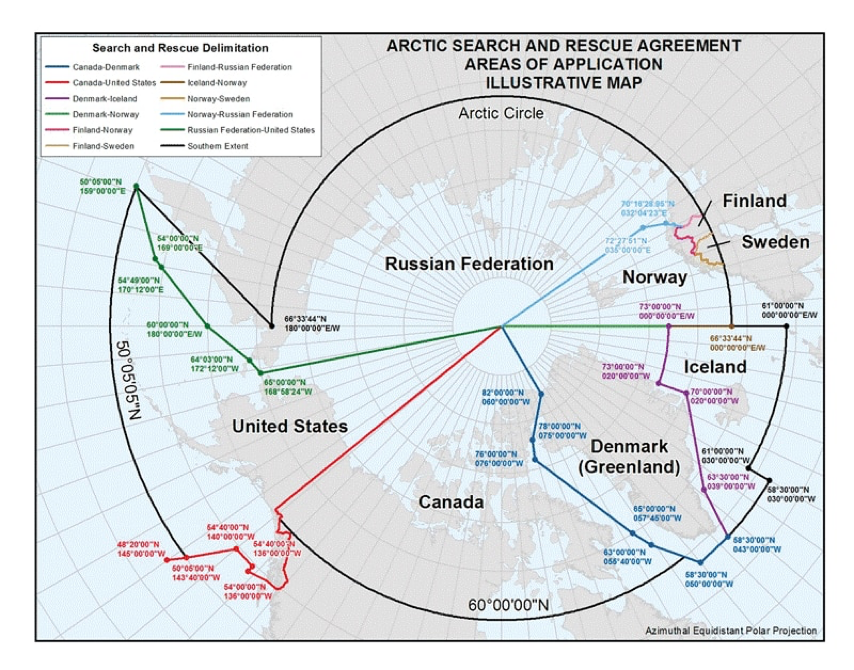

The Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement was the first binding agreement negotiated under the auspices of the Arctic Council and was signed in May 2011 in Nuuk, Greenland. The agreement paved the way for even greater regional cooperation among the Council’s member states.

The Arctic SAR Agreement accomplished three major tenets: first, it established boundary lines across the Arctic that delimitate which party is primarily responsible for rescue operations. Second, the agreement establishes a requirement for all parties to create and maintain Rescue Coordination Centers (RCCs) and to make those centers available for coordination. Finally, the agreement establishes lines of communication, including a general framework for regular coordination meetings. Overall, the Arctic SAR Agreement is a straightforward and simple document, as far as multi-party international agreements go.

However, the Arctic SAR Agreement has some significant limitations. Since the Arctic Council is a forum, it has no budget to allocate to specific projects. Thus, the Arctic SAR Agreement does not allocate any money to rescue operations or mandate the expenditure of funds by participating parties.

Moreover, the agreement does not establish any new or unique SAR procedures. The agreement relies on parties utilizing the SAR Convention and the International Air and Maritime Search and Rescue (IAMSAR) Manual for procedures and coordination processes.

The agreement does not establish a minimum SAR capability threshold for any of the parties. There are no requirements for aircraft or vessel capabilities, such as rotary-wing hoist, transit speed, or aerial refueling capabilities. Most importantly, the agreement does not establish any asset response time requirements or recommendations.

Finally, while the agreement encourages parties to share asset information, it does not establish a central database of ports, airfields, rescue assets, alert status, or response times. This creates an information vacuum that RCCs must fill on a per-event basis or “as able.”

The Next Step for Assuring Rescue

Development activities in the region will undoubtedly be a mosaic of multiple governments and private industry. It is the role of governments to enable regional development and steer activities to be conducted sustainably. The Arctic Council should revisit the Arctic SAR Agreement and make the following improvements, for the sake of sustainable development:

- Charter a committee on Arctic SAR improvement and establish meeting frequency requirements and a minimum number of multinational exercises per year.

- Appoint a party to create and maintain a database, or common operating picture (SAR COP), of available national, local, and private SAR assets. This can be contracted to private industry, perhaps led by companies with large stakes in Arctic development.

- Establish a requirement for all parties to feed their data to the SAR COP and report estimated response times for the entirety of their respective SAR regions.

A Dose of Reality

As much talk as there has been about a warming Arctic, Arctic nations have not yet been able to develop new infrastructure to support search and rescue operations. Companies are making preparations to increase their operations in the High North and have their eyes on profits. The smartest of those companies will put resources into assessing their risks in operating in such a remote and harsh environment.

Given the small number of binding multinational agreements the Arctic Council has managed to shepherd, perhaps there is a need for a new multinational framework that can ensure safety and security in the non-Russian Arctic. For now, Arctic search and rescue remains a largely unanswered problem set and the Arctic Council, finally led by a responsible party, has the opportunity to shape the environment in a way that enables responsible and sustainable growth and development.