+ The commercial space sector is booming, with the U.S., UK, China, India, Singapore, Brazil, and the UAE all experiencing significant growth amidst increased state investment.

+ As both companies and nations forge ahead with their space capabilities, astropolitical risk looms large, as earth-borne geopolitical competition deems to defy gravity.

+ These risks are compounded by fragmented governance regimes that give way to legal disputes over fault in space accidents, politicization of even mutual-interest endeavors such as banning anti-satellite weapons, and concerns about dual-use and gray zone activity.

+ When states attempt to fill these gaps, they frequently do so unilaterally, creating tensions amongst themselves and thereby exacerbating the cycle of geo- and astropolitical risk.

Space infrastructure underpins virtually every aspect of contemporary life, from economic and social systems to security measures. Over the past two decades, space has transformed from a state-dominated political and scientific sphere into an increasingly commercialized and diverse market. The global space economy, valued at $447 billion according to the Space Foundation, is anticipated to reach an impressive $2.7 trillion by 2040. This represents a growth rate of 176% since the Space Foundation’s initial analysis in 2005. As a new “lift off” sector, space is characterized by high barriers to entry, and highly prized rewards. In this environment, geopolitics and regulatory confusion combine to create significant uncertainty for the burgeoning commercial space industry.

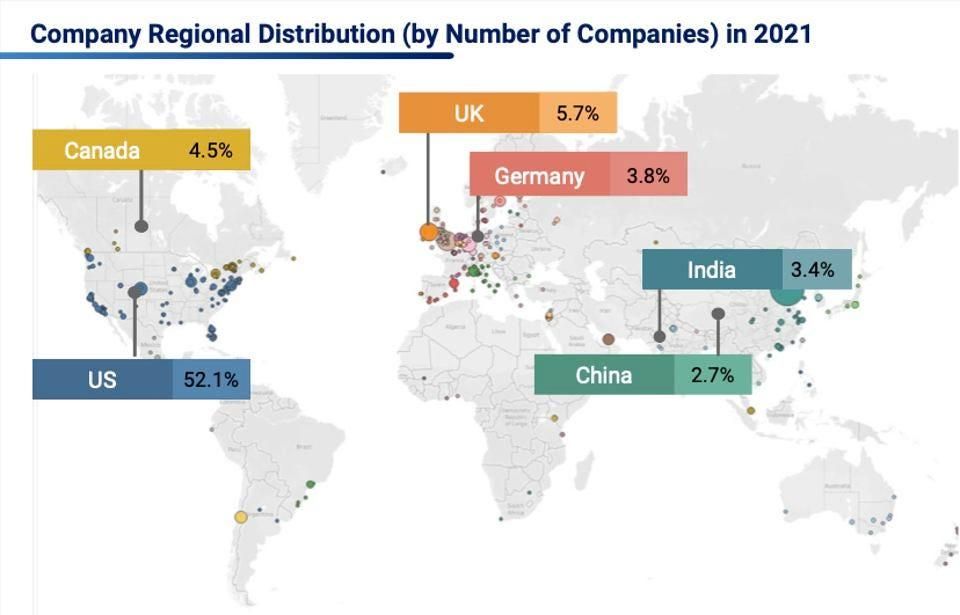

In the UK, a small space player compared to the U.S., the number of space-related companies grew from 948 in 2016-17 to 1,218 in 2018-19. The expansion of the UK’s space industry remained robust through the financial storms of Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic as the private sector, backed by feverish government and public interest, raced to meet new demand. Furthermore, this trend is mirrored globally: in India for example, the total number of local commercial space start-ups grew almost 15% between February 2020 and the end of the same year, with its space sector expected to expand from a $7 billion industry to a formidable $50 billion by 2024.

Meanwhile, despite Beijing’s heavy historic focus on state-owned enterprise for the space sphere, China’s commercial space sector has developed rapidly. While all aspects of China’s space sector remain beholden to Beijing, it now boasts 78 space-related commercial companies, with 45 of those having been established since 2015 when some restrictions on commercial space companies were lifted. Similarly by 2021, Singapore, Brazil, and the UAE could boast 97, 94, and 41 commercial space sector-related companies, respectively.

Astropolitics: Re-launching Geopolitics into Space

Nevertheless, the enormous potential of the growing “new space” economy is threatened by a mainstay of the “old space” era: geopolitical competition. In this new era of competition characterized by a rapidly growing milieu of interests and actors, the geopolitics of space is now expanding into full-fledged astropolitics. As space becomes a new frontier for commercial activity, accessible to an increasing number of actors due to technological advances and cost reductions, it concurrently becomes a new battlefield in the global shift toward multipolarity.

While astropolitical competition is undeniable, and emerging norms are frequently contested, this contest is not a reincarnation of a Cold War clash between democracy and authoritarianism.

In this environment, the global order is becoming increasingly contested between the U.S., China, EU, Russia, and an array of influential “middle powers.” While astropolitical competition is undeniable, and emerging norms are frequently contested, this contest is not a reincarnation of a Cold War clash between democracy and authoritarianism. It is, instead, a complex struggle over differing interpretations of global governance, mired in national interests. The result is that the lines between civilian and government ventures increasingly blur.

Development into new frontiers such as space is becoming a simmering combination of competition, cooperation, and strategic rivalry which must be concurrently managed by government or private actors on a topic-by-topic basis–intensified by the rapid pace of technological advancement. The implications for commercial space enterprises moving forward cannot be understated. This astropolitical complexity yields a greater susceptibility to risk from state and non-state actors alike: from civil-military fusion, dual-use infrastructure, and gray-zone strategies to the weaponization of economic, commercial, or treaty negotiation processes. Astropolitical competition also means that sovereign control, national resilience, and agency of action have become more important for governments as states attempt to navigate this new environment, seize its opportunities, and manage its risks.

Fragmented Governance and Competing Regulatory Regimes

The perception of these risks can undermine trust between nations, hampering the formation of international agreements needed to manage competition and further complicating the regulatory landscape. For commercial enterprises, these developments create fundamental operational uncertainties and elevate the risk of legal disputes, potentially deterring much-needed investment in this capital-intensive sector. International attempts to clarify existing regulations have often resulted in governments adopting their own potentially conflicting interpretations, adding to this uncertainty.

For instance, the absence of a universally accepted definition of “fault” under the Outer Space Treaties Liability Convention can lead to disagreements in the event of an incident involving space infrastructure. Even areas of apparent mutual interest, such as banning kinetic anti-satellite weapons due to their debris-producing nature, have become politicized as national governments attempt to safeguard their own agency while limiting others.’ That space technology and infrastructure can easily become dual-use and utilized in gray zone activity is a further bottleneck to progress, compounded by the treatment of space as a military domain by the U.S., China and others.

Attempts to unilaterally bridge these gaps in space governance, such as the US-led Artemis Accords, have created international controversy. The Accords, already at odds with the 1979 Moon Agreement and its signatories, are viewed by competitors like China as a rival framework; such actors may indeed be motivated to put forward their own. The risk here is not that space becomes a Wild West, but rather its governance becomes fragmented, with competing regulatory regimes that may not be compatible or even recognize each others’ legitimacy.

Geopolitical tensions on Earth are threatening to spill out into space. The regulatory and operational environment for commercial enterprises entering the space domain is increasingly precarious, as access to critical supply chains and even seemingly minor national regulations, such as merger reviews, can be weaponized. These conditions underscore the need for basic international agreements to foster a secure and sustainable development of the commercial space sector. The challenge ahead for those engaged in astropolitical competition is not only to foster commercial expansion into space, but ensure the potential of the new space economy is not left scuttled by Earth-bound geopolitical wrangling.