Deep Sea Mining & Green Energy

At first, it's just that environmental and extraction costs are too high--then you realize these minerals drive the Green Revolution, and there's a national security need for sovereign supply of them outside China and Russians.

Introduction:

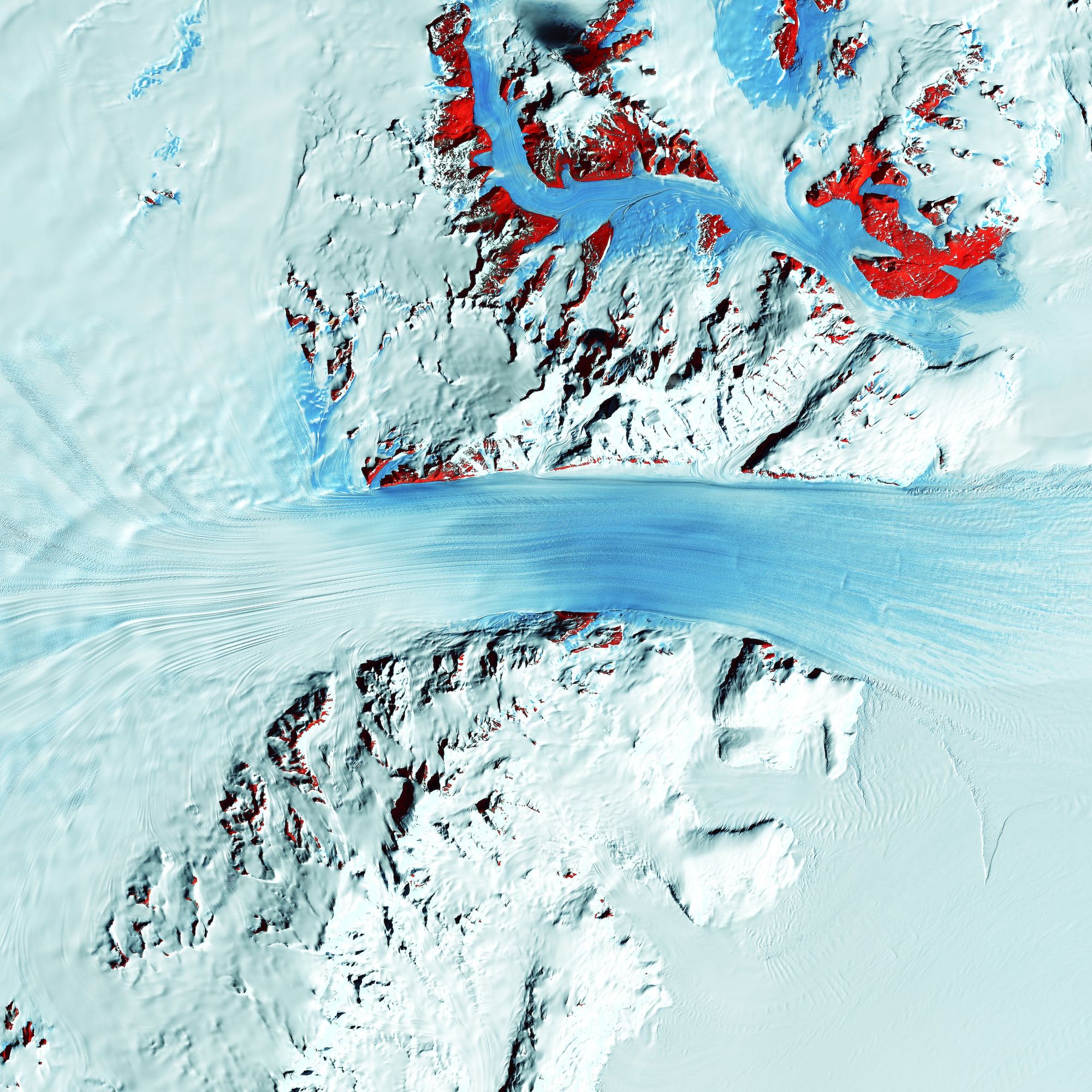

The British Antarctic Survey has highlighted that complete ice melt in the Arctic is now possible as early as 2035. While such an acceleration may cause on a conservative estimate $24.8 trillion in permafrost damage within the Arctic. The easing conditions also increase the cost-efficiency of economic activity and decreases logistical costs for the region, facilitating new opportunities and industries. Often overlooked in the discussion around these new opportunities; which amplify oil, the region's shallow gas hydrates, or opening shipping lanes, is climate change’s facilitation of Arctic deep-sea mining. Indeed the Arctic is in the near future a prime candidate potentially for such activity, given the political, geographic and economic advantages that the Arctic Ocean’s seabed has over those of other oceans. The geopolitical consequences of such a developing industry in the region would also be significant.

Impact:

Deep-sea mining in the Arctic is potentially set to create significant ruptures in the diplomatic relations of states within the Arctic due specifically to two factors this paper explores.

- Firstly, by increasing the geopolitical importance of seabed claims that converge in the region, as states seek to expand and consolidate critical minerals to take advantage of an impending upscale in demand and to facilitate strategic independence as critical mineral supply chains become politicized in a multipolar world.

- Secondly due to emerging differences between polities regarding what climate mitigation policy should and should not contain. Deep-sea mining occupies a contested and controversial place in regard to climate change, and it has cross-border and indeed potentially global consequences. States and companies engaging in it, particularly in the ecologically fragile Arctic will attract significant external scrutiny.

Deep Sea Mining in the Arctic:

Deep Sea mining is a resurrected emerging industry, having started in the 1960s and developing significantly before its decline in the 1980s due to high costs and the dissipation of fears surrounding the politicization of mineral supply chains for political aims through “commodity power”. This current iteration of the industry however has a new angle, with its advocates linking it to climate change alleviation. This is based on increasing populations in Asia and Africa demanding goods and technology, compounded by the drive for a global “green revolution” in technology and energy. For instance electric vehicles require six times the mineral input than a standard vehicle. All of this requires greater access to minerals to meet demand, particularly as states begin to increase their stockpiles to cover their expected needs and due to the politicization of the mineral supply chain stemming from increasing state competition, and a rekindled fear of “commodity power” abuses of critical minerals, though this time with some foundation.

OK, so this is how we can use custom fonts. HTML card. Ok, we can work with this I suppose. Getting Closer. This is Poppins from our site for example, but we don't have to use it. For more supported fonts, chatgpt knows ;p

This rekindled interest in deep-sea mining will see the Arctic Ocean adopt an increasingly prominent role that goes radically beyond its previous utilisation as a source of tin for the Soviet Union. The Arctic Ocean was where polymetallic nodules, a key source of minerals for seabed exploitation were first discovered in 1868. The region contains known quantities of critical mineral sources necessary to help alleviate increasing demand over the coming decades, the scale of which is currently unknown, with more potentially to be found. This includes rare earth elements, iron, gold, silver, nickel, copper, and zinc. These are some of the very critical minerals that will be in most demand, particularly for the green revolution.

Comparative Advantages

The Arctic Ocean is the shallowest of the earth's five oceans, its deepest point has a depth of 5573 metres, though its average depth is only 987 metres. By comparison, the Pacific Ocean, where most deep-sea mining exploration is currently taking place, has an average depth of 4,000 metres. This includes its Clarion-Clipperton Zone which is the current global hub of deep-sea mining activity.

More than simply containing needed resources, the Arctic, and its Transnational area will be an attractive proposition comparatively for deep sea mining exploration and exploitation over the coming decades compared to both land-based and other seabed alternatives.

Depth is incredibly important as a financial buffer for deep-sea mining operations. The deeper the minerals are the higher the complexity, logistical cost, and risks to the operation will be. Historically this issue of cost-effectiveness at varying depths was a significant contributory factor in the 1980s halt of the industry as mineral prices having been inflated prior to 1974 began a long decline due to more efficient land-mining and resource utilization, and a wider global slowdown in productivity.

Currently, however, critical land-based mines are beginning to see a terminal decline in ore quality, increasing extraction and processing costs. This is set to significantly affect their profitability in the near future. This will be at a point when deep sea mining in the Arctic can harvest both multiple ore types and rare earths potentially from one site, and as seabed mined ores will be of higher grades and potentially more cost-effective. Particularly as on average 99% of a seabed deposit is potentially usable material compared to around 20% for land-based sources.

Aiding Deep Sea Minings interest, mineral prices have been, and continue to rise due to increasing (both real and expected) demand to fund the green revolution. In this context the shallower Arctic provides potentially a greater degree of price security for deep-sea mining. Even if critical mineral prices begin to taper off as new sources are found in the coming decades, its operating costs theoretically should be lower as the Arctic’s conditions ease, and so profit margins higher, compared to its land-based or other-ocean counterparts.

Why in the Arctic?

The Arctic has two further aspects in its particular favour even compared to the wider Arctic. Firstly, the comparatively shallow Arctic Ocean also has a significant number of hydrothermal vents. These are vents where concentrations of minerals such as copper, gold, and zinc are usually found in significant quantities. Secondly, as nearly all the Arctic Ocean seabed in the Arctic is currently administered or claimed by a sovereign state, with submissions pending with the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) to arbitrate most remaining areas,

we can do columns!

nearly all deep-sea mining sites will eventually be under a sovereign national jurisdiction. This potentially means plentiful opportunity for seabed mining companies to seek preferential treatment, playing on economic competition between states and taking advantage of far more dynamic or favourable tax or policy regimes. None of which is possible for operations that fall within the international seabed, and so are beholden to the International Seabed Authority (ISA) as most Pacific seabed mining will be.

FIN

Fin.