+ Iraq’s fragile recovery is threatened by its heavy dependence on oil and ongoing security and political challenges.

+ Insurgent groups like IS remain capable of exploiting vulnerabilities, while the IRI exerts destabilizing influence through militia interference, and the PKK disrupts security in northern Iraq, particularly near the Turkish border.

+ Oil accounts for the vast majority of Iraq’s budget, making the economy highly vulnerable to price shocks; while alternative energy projects show promise, they remain underdeveloped and face risks from insurgent activity and inadequate infrastructure.

+ The Development Road megaproject illustrates the intersection of Iraq’s security, economic, and political risks. While it offers transformative potential, threats from armed groups, oil dependency, and political instability could derail the project, undermining Iraq’s broader reconstruction and stability.

Amidst escalating hostilities across the Middle East owing to the conflicts in Gaza and Lebanon, the matter of Iraqi stability has recently come under renewed focus. Far from the political disarray and chronic insecurity that facilitated the rise of groups such as the Islamic State (IS), the country today appears to be making strides towards reconstruction. Bolstered by elevated global oil prices, Iraq's GDP has grown steadily, with projections indicating continued growth in the coming years. A number of sectors such as construction and real estate witnessed particular growth as the country undertakes ambitious reconstruction and infrastructure projects.

The Iraqi Government, eager to capitalize on oil revenues and prevent a resurgence of conflict, has sought to diversify its economy and build resiliency, while creating a more inviting climate for foreign direct investment (FDI). Although numerous concerns around militia impunity, rule of law, corruption, and continued IS insurgency remain, Iraq has not slid into full-scale conflict as many had feared.

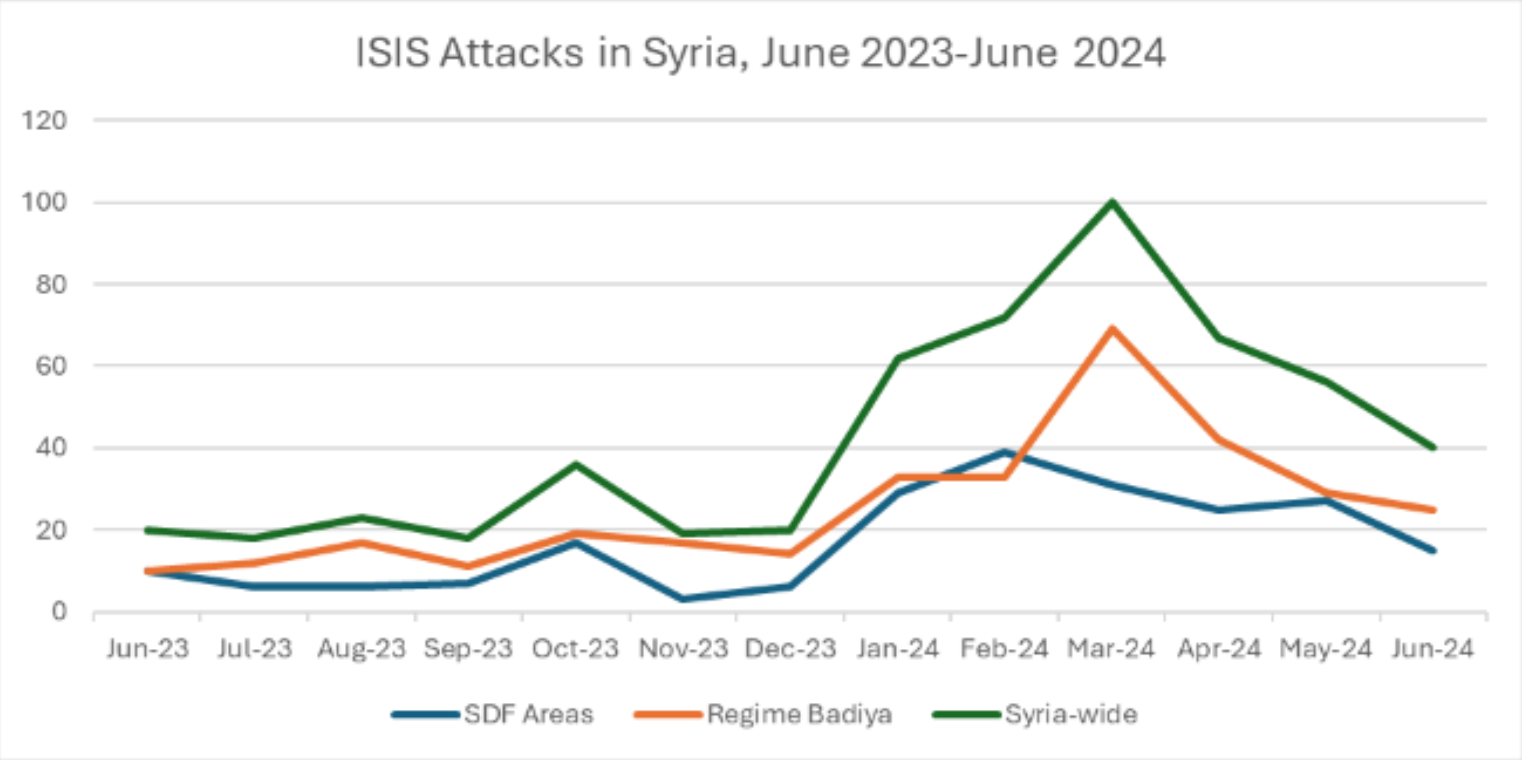

Nevertheless, a report published by the United States’ Central Command (CENTCOM) in July 2024 raised concerns about whether this trend of stability can be maintained. In the report, CENTCOM warns that the rate of IS attacks in Iraq and Syria had already outpaced the number of attacks in 2023. It estimates that at the current rate, total attacks in 2024 will surpass the 2023 rate by about double.

Iraq can ill-afford to return to an era of renewed internal conflict, which could not only reverse the hard won gains made since the territorial defeat of IS, but also painfully undermine confidence in the country’s recovery.

This article examines the CENTCOM report in order to untangle the implications of a resurgent IS. It finds that much of the IS threat remains focused in Syria, with the group’s presence and activity in Iraq on a steady downward trend. Overall, this article also posits that Iraq does not face an existential threat from a single organized armed group. However, the multitude of armed groups in the country (including IS) retain the ability to strike at vulnerable industries and infrastructure. This can hinder critical development efforts, eroding stakeholder and investor confidence in Iraq’s reconstruction.

Furthermore, the Iraqi economy–and likely the functioning of the state itself–remains reliant on oil revenue. Although the Iraqi Government continues to emphasize the need to diversify, there are signs that the rentier model that emerged after 2003 is set to persist. While sustained global demand for oil may temporarily lessen the urgency for reform, global trends, such as cooling demand in China, indicate that Iraq faces both fiscal and time pressure to implement reforms that foster a more resilient economy.

The Development Road megaproject proposed between Iraq, Türkiye, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) illustrates the current risks facing Iraqi reconstruction more broadly: the ambitious project, if successful, would boost returns across numerous sectors that are already seeing healthy growth in Iraq. However numerous challenges—from insurgencies to criminality to political paralysis—all run the risk of derailing the project. Should the stability and economic growth represented by the project fail, IS would be among the biggest winners.

CENTCOM Warns of IS Resurgence

CENTCOM, responsible for overseeing the ‘Defeat ISIS Mission in Iraq and Syria,’ issued an unusual press release on 16 July 2024. In this update, CENTCOM warned of a significant increase in the number of attacks claimed by IS in 2024. Specifically, CENTCOM warned that the 153 attacks claimed by IS in Iraq and Syria has already surpassed the total for 2023, and cautioned that if this trend continues, the total number of attacks could double compared to the previous year's figures.

CENTCOM described the growing pace of attacks as part of the group's efforts to reconstitute itself following the loss of its last territorial holdings in Syria in 2019. The statement noted that security operations against IS will continue in collaboration with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF). The release also posited that a suspected 2,500 IS militants remain at large, with another 9,000 still held in detention facilities in Syria.

Current Challenges for Iraqi Security

The Islamic State

Following the liberation of Mosul and other Iraqi urban centers from IS fighters in 2017, experts widely anticipated that the group would go underground, and revert to insurgency tactics. This prediction was based on both the group’s historical behavior–retreating underground and regrouping following each major defeat–as well as communications from within the group itself.

This assessment proved accurate. Starting in 2018, the group launched an insurgency campaign in Iraq and Syria, attacking soft targets, infrastructure, community leaders, and military forces. The campaign in Iraq peaked in the second quarter of 2020 with 808 IS-initiated attacks, a surge partly attributed to reduced patrols and military operations due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the group struggled to sustain any momentum, and attack patterns became erratic in the early years of the pandemic. While IS was able to carry out a number of major attacks in 2022–such as the killing of 11 Iraqi soldiers in Diyala, and the prison break in Syria’s Ghweran–overall attacks in Iraq have trended downward. In 2023, the country recorded its longest period of stability with a functioning government since 2003, as well as a decline in the level of terrorist violence to pre-invasion levels.

As such, it is important to consider the CENTCOM warning with some context.

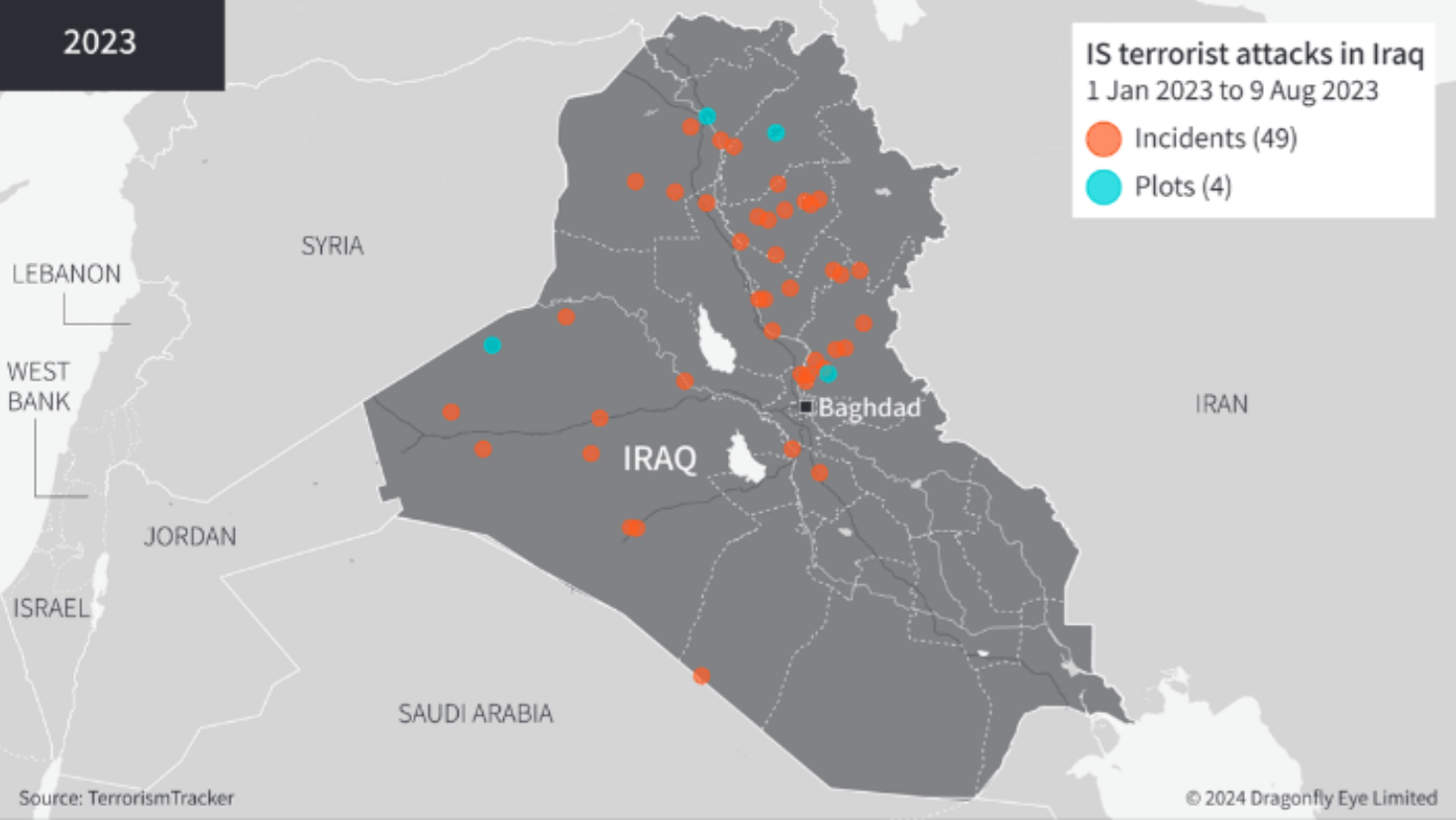

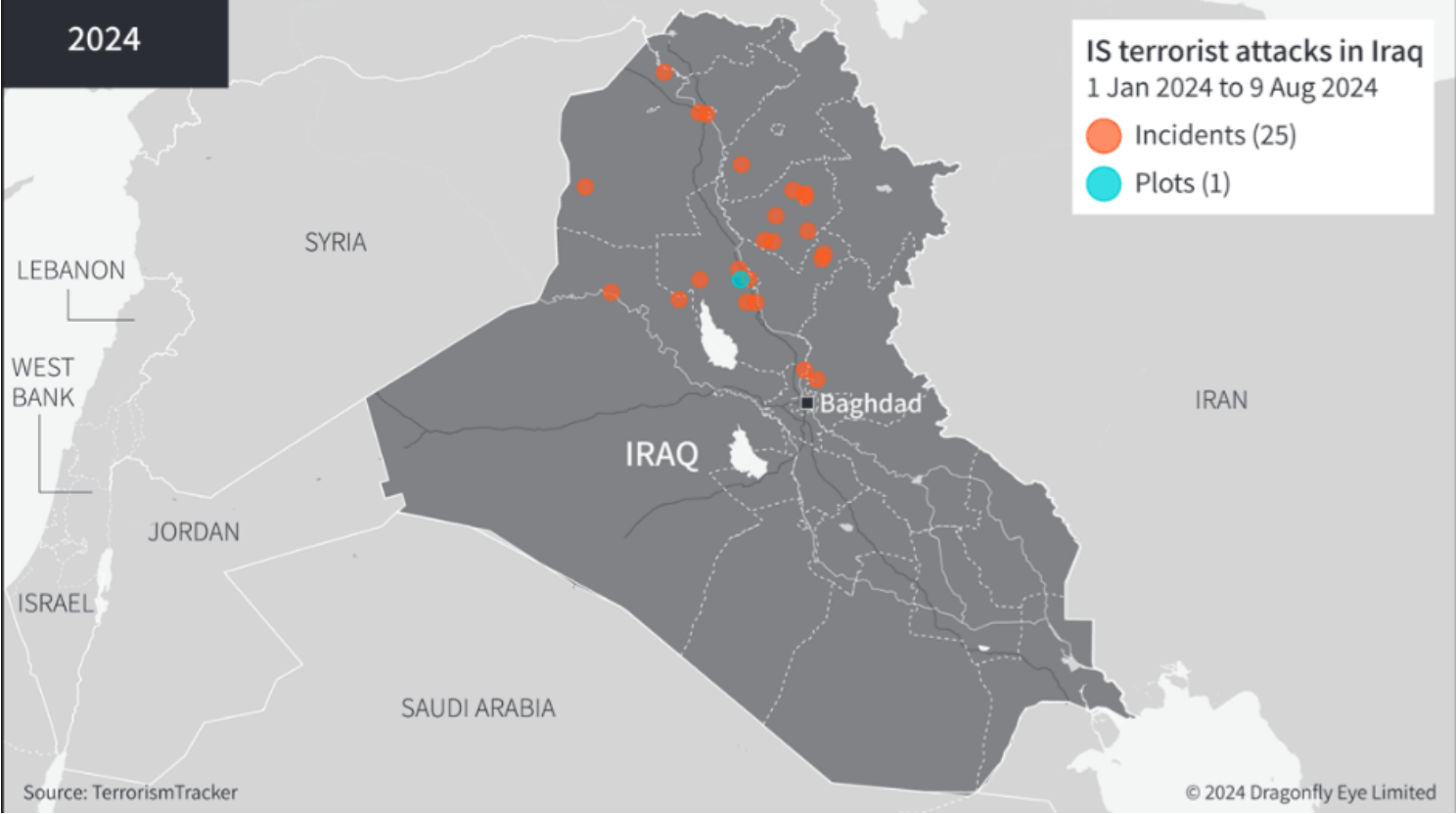

While the CENTCOM press release highlighted a rise in IS attacks in Iraq and Syria, it did not specify the number of incidents in each country. Analysis by the intelligence firm Dragonfly recorded 25 IS-linked attacks in Iraq between January 1 and August 9, 2024, marking a significant decrease from the 49 attacks reported during the same period in 2023. Furthermore, the 2023 attacks spanned a much wider geographic area compared to 2024, a year which has seen no incidents in Anbar Province, once considered the group’s primary base of operations. Instead, recent attacks have been concentrated in central and northern provinces, including areas on the outskirts of Baghdad, Diyala, Salah ad-Din, Nineveh, and Duhok.

It appears that many of the IS attacks referenced by CENTCOM occurred in Syria, particularly in the Syrian Desert, a region known as the Badiya, and now controlled by forces loyal to Damascus. The frequency of attacks has increased following the redeployment of Russian and Iranian forces to other theaters in response to developments in Ukraine and Gaza, providing IS room to operate with relative impunity.

Perhaps more concerning, analysts comparing IS-claimed attacks with local reports and insider accounts suggest that IS appears to be undercounting its attacks in the region. It remains unclear whether this discrepancy stems from communication challenges between local cells or a deliberate strategic communications effort to rebuild its strength without attracting global attention. Nevertheless, in combination with renewed unrest in areas like southern Syria, there is a substantial risk that IS could exploit the current context to reconstitute itself and regain a foothold in the country. Should this occur, it could eventually threaten Iraqi security by exploiting the extensive, porous border between the two countries.

In combination with renewed unrest in areas like southern Syria, there is a substantial risk that IS could exploit the current context to reconstitute itself and regain a foothold in the country.

Operating within similar constraints, during the 2010s, IS capitalized on the escalating conflict in Syria to build its power base before advancing into Iraq, leveraging the recent U.S. troop withdrawal and worsening political conditions there. Today, there is a real and pressing risk of history repeating itself, as Baghdad considers withdrawing U.S. troops, citing IS’s weakened state in Iraq and escalating tensions with Washington over the conflicts in Gaza and Lebanon. However, while IS remains the primary threat to Iraq’s stability and reconstruction, it is by no means the only armed group posing such risks.

The IRI and the Wider Militia Movement

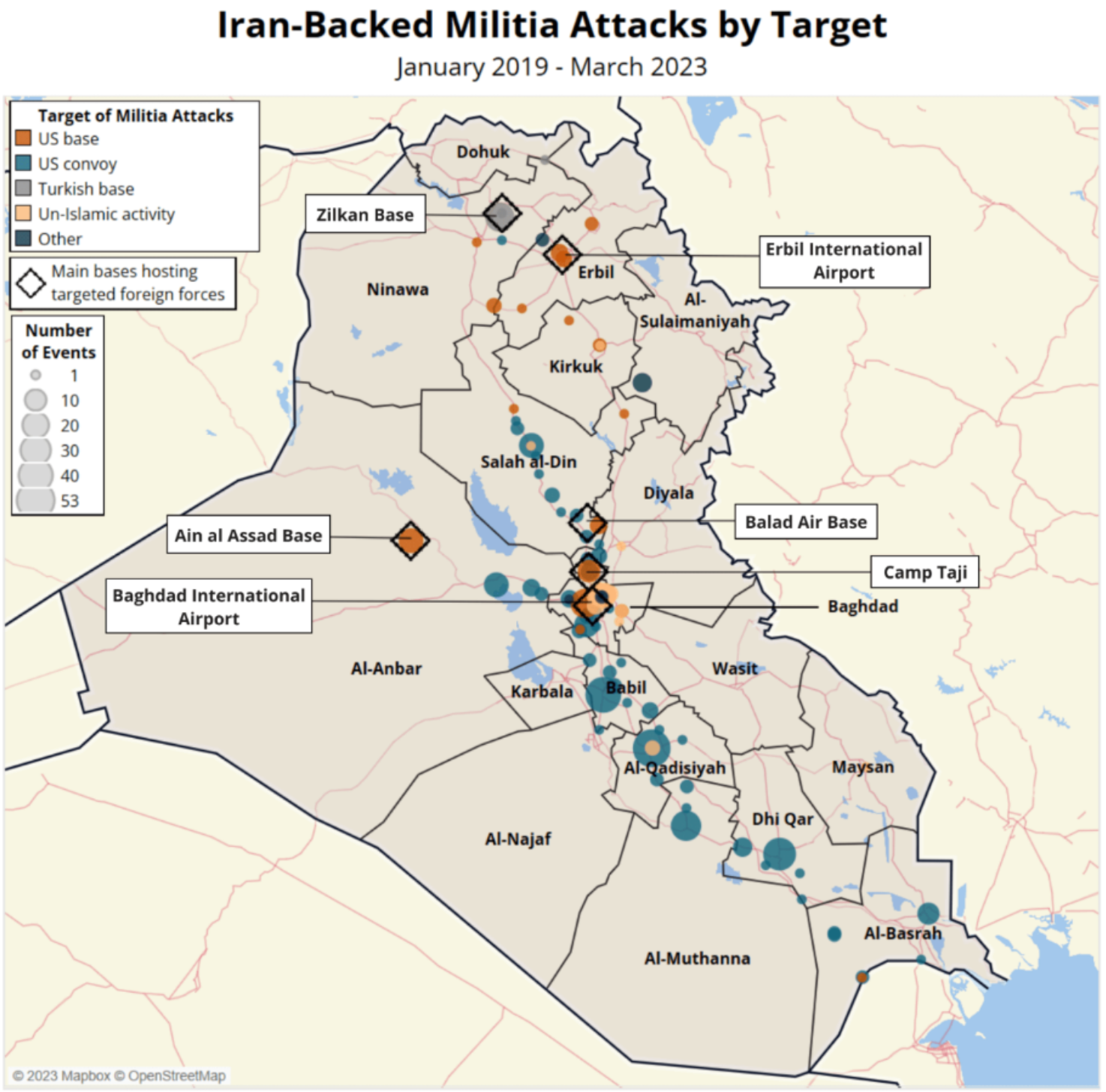

The Islamic Resistance in Iraq (IRI) is still a relatively little-known armed faction that emerged within the context of the ongoing conflict in Gaza. The group has conducted multiple attacks on U.S. security installations and bases across Iraq. These attacks were geographically dispersed, targeting locations such as Ain al-Asad Base in Anbar, Harir Airbase near Erbil, and a U.S. convoy near Mosul. The group is also believed to be responsible for drone attacks on the Tanf Base and the Conoco oil field in Syria.

The exact composition of the IRI remains unknown, as the group’s statements deliberately obscure its structure and exact components. However, it is widely believed to be comprised of militia groups and factions of the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) tied to Iran, particularly those based in southern provinces such as Basra. This assessment is supported by statements from members of Iran-aligned groups such as Kata’ib Hezbollah and Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada, which align with the IRI’s objectives. Nonetheless, the IRI has, to date, been careful not to directly implicate these more established groups in its own attacks.

The U.S. sees the IRI as an arm or proxy of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and retaliatory U.S. strikes on the IRI have regularly targeted the IRGC and its affiliated factions. U.S. statements referencing IRI activities often highlight the role of Iran and the IRGC in IRI activity. The IRI’s main objective appears to be pressuring Washington into fully withdrawing its forces by targeting U.S. interests in Iraq. While the group has not conducted known attacks on Iraqi civilians or state infrastructure, it has actively pressured Baghdad to fully expel U.S. forces. Given the close ties between Iran and Iraq’s current government—led by the Coordination Framework Bloc—it is unlikely that the IRI is currently plotting against the Iraqi state, for the time being.

However, the IRI—and more specifically, certain factions within it—continues to threaten Iraq’s security and stability through criminal and subversive activities. In the summer of 2024, two Iran-backed factions, Kata’ib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, were found to be engaged in oil smuggling operations in southern Iraq, a key source of funding for these activities. These groups have also been implicated in drug smuggling and violent attacks on protesters in Basra. In the past, these militias have disrupted numerous investment initiatives for the direct benefit of specific foreign investment groups. In one example, the al-Faw Port project spearheaded by the South Korean company Daewoo was nearly derailed due to militia interference in favor of an unidentified Chinese company. The influence these factions exert over projects like the construction and operation of the al-Faw Port and the broader Development Road could intimidate investors, particularly those from the Gulf who are wary of Iran.

The al-Faw Port project spearheaded by the South Korean company Daewoo was nearly derailed due to militia interference in favor of an unidentified Chinese company.

Beyond these immediate risks, the activities of the IRI increase the likelihood of Iraq being drawn into the crossfire between Iran and Israel, as evidenced by Israel’s responses to attacks from both Lebanese Hezbollah and the Yemeni Houthis. In September 2024, the IRI claimed responsibility for a drone attack on Israel’s Eilat port, heightening the possibility of Israeli airstrikes on Iraqi territory. This development—amid on-going Israeli operations in Lebanon and a concurrent ground offensive there—could significantly alarm investors and stakeholders, particularly given the Port’s close proximity to Iran, the presence of Iran-aligned militias, and associated patterns of criminal behavior.

The Kurdistan Worker’s Party

The Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) is an armed group that has conducted attacks against the Turkish military since the 1980s. Much of the group’s leadership is believed to be based in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), with a documented presence in the Dohuk and Erbil Provinces, the Asos Mountains in Sulaymaniyah, the Qandil Mountain Range along the Iraq-Iran border, and the Makhmour and Sinjar Districts in Nineveh. The PKK is designated as a terrorist organization by Türkiye, the United States, and the European Union.

The group has troubled relations with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG); the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) is openly hostile toward it, while the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) remains neutral to somewhat supportive. The PKK’s primary focus is Türkiye, and it generally refrains from targeting Iraqi or KRG interests, instead using Iraq as a base for operations against Türkiye or attacking Turkish interests within Iraq. Türkiye, over decades, has launched numerous air campaigns and ground operations against the PKK in Iraq, often straining relations between Ankara and Baghdad. Ankara, in particular, has consistently urged Baghdad to take action against the PKK.

The PKK’s aversion to antagonising Baghdad may shift in the coming months: in March 2024, Iraq’s National Security Council officially banned the PKK following a visit from Türkiye’s foreign and defense ministers to Baghdad. Since then, Türkiye has announced new military operations against the PKK in both Iraq and Syria.

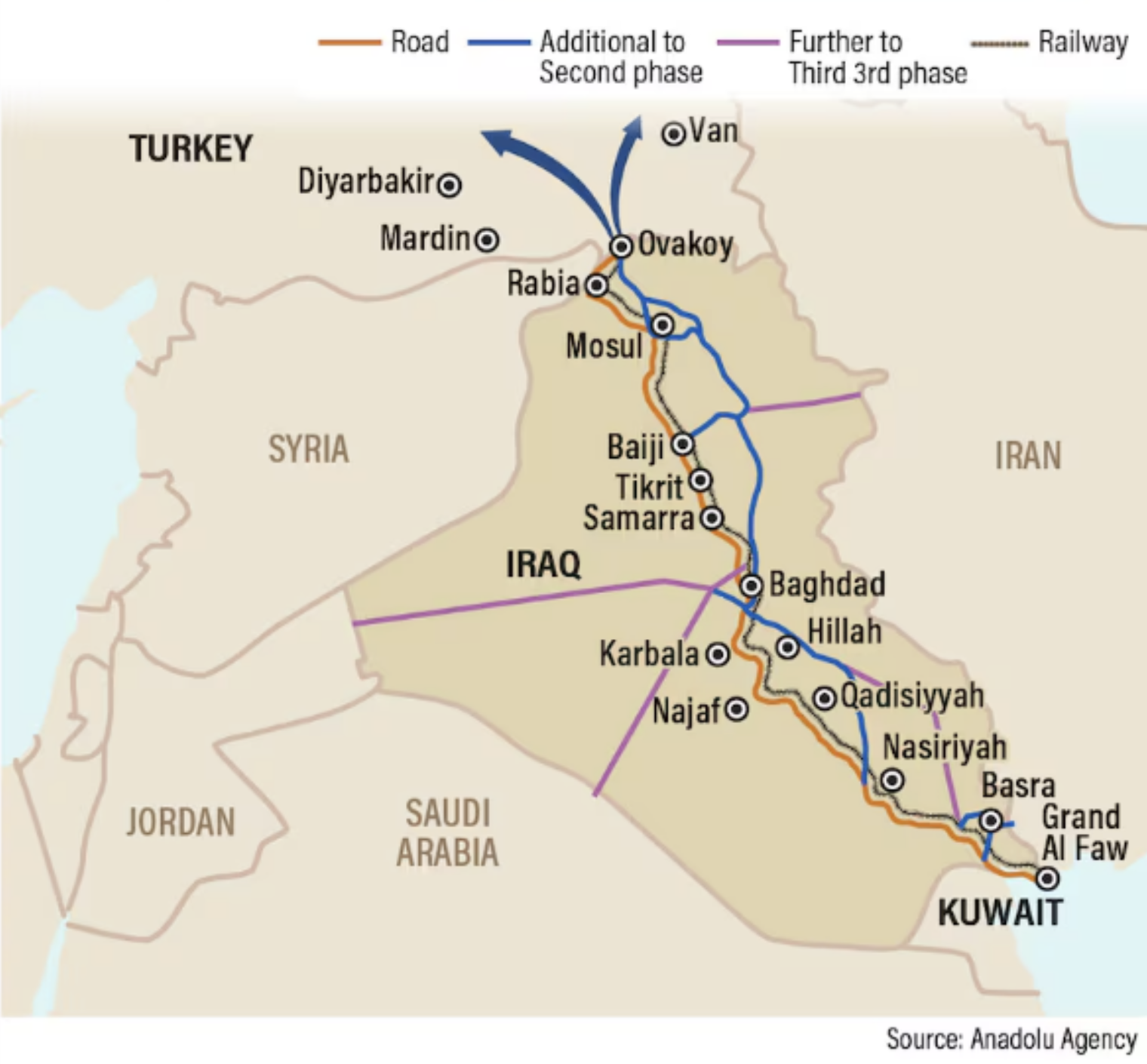

The growing alignment between Ankara and Baghdad appears to be partially motivated by the Development Road, a planned megaproject that envisages upgrading Iraq’s al-Faw Port in Basra and enhancing transport from Basra in the Gulf to the Turkish border in northern Iraq, where the PKK is active. This project would allow Iraq to become a transit route for goods destined for the EU. Many analysts and officials have linked Türkiye’s pressure on Baghdad regarding the PKK to the multi-billion dollar Development Road initiative.

The interconnection between the Development Road and Turkish operations, however, makes the project a tempting target for parties looking to act as spoilers. The PKK, in particular, may be incentivized to increase the number or severity of its attacks on Turkish interests and could potentially begin targeting the ISF, though this remains a low likelihood. While the PKK likely lacks the military capacity to fully counter joint operations by Ankara and Baghdad, the emergence of soft targets related to the Development Road may still enable the group—with its decades of guerrilla warfare experience—to render the project unprofitable.

Thus, while the PKK does not represent a direct threat to Iraqi stability and security, it is nonetheless well-positioned to disrupt one of the country’s most ambitious economic and political projects in decades. Ankara appears aware of these risks and has sought to create buy-in from Kurdish factions, as well as from Iran, to prevent interference, bolster the success of its operations, and politically and economically isolate the PKK.

As a result of the prevalence of such armed groups and Iraq’s comparatively limited capacity to address multiple sources of unrest, there is a risk that even a single armed group could trigger a chain of events with broader ramifications for Iraq’s stability and security. This is particularly concerning in the context of Iraq’s economy which, despite strong growth in recent years, still exhibits clear risk factors.

Current State of the Iraqi Economy

Currently, the Iraqi economy is on a path to recovery. Following the territorial defeat of IS, the country made important strides toward reconstruction, attracting FDI, and fostering stability. However, progress remains uneven, and the economy is still highly sensitive to both internal and international developments.

The uneven pace of Iraq's economic development is clearly reflected in its fluctuating GDP over recent years. In 2014, Iraq's GDP reached a high of $234 billion but declined significantly following the emergence of IS, dropping to $192 billion by 2017. After a period of recovery, GDP peaked again at $232 billion in 2019. However, in 2020, the pandemic triggered a sharp decline in global demand for oil and gas, causing Iraq's GDP to plummet to $181 billion, underscoring the country's vulnerability to commodity price shocks. Since then, Iraq's GDP has rebounded alongside the return of oil demand, peaking at $261 billion, with only a slight contraction of 2.9% in 2023. The Iraqi government anticipates a further GDP contraction of 0.3% in 2024. Nonetheless, the overall trend remains positive, with analysts expecting significant economic growth between 2025 and 2029

Unsurprisingly, much of Iraq’s economic growth was fostered by its main export: oil. The reliance on a single extractive commodity has resulted in Iraq suffering from all of the hallmarks of a rentier economy: corruption, macroeconomic volatility, budget rigidity, high unemployment, and uneven taxation.

In an effort to diversify away from oil revenue, Baghdad has embarked on a campaign to foster the private sector and improve the country’s investment climate. In June 2024, Baghdad took further steps toward becoming an investment destination by signing the United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation, commonly known as the Singapore Convention. This agreement facilitates the enforcement of cross-border mediated settlements, supporting international trade and commerce and bolstering anti-corruption measures. Iraq has also begun reforms to modernize its tax system, which has faced criticism for its structural complexity and inadequate enforcement mechanisms.

These efforts to attract FDI have yielded some important results. Gulf states, in particular, have shown strong interest in Iraq, with investment primarily flowing into the real estate and construction sectors. Although some of these investments are motivated by political goals, namely attempting to balance Iran's role in the country, the improved investment climate has almost certainly been a driving factor. China, a purchaser of around 35% of Iraqi oil annually, has also emerged as a major investor, particularly in the energy sector. As a result of these trends, Iraq saw a record FDI inflow of $24 billion in the first nine months of 2023.

However, many economic institutions such as the World Bank warned that the 2023-2024 budget remains “excessively expansionary” and lacking in many of the structural and fiscal reforms required for a sustainable economy. This assessment suggests that Iraq’s current development model, which is highly dependent on oil, is unlikely to change in the near term. Consequently, Iraq's economic prosperity will remain closely tied to oil for the foreseeable future.

Oil and the Energy Sector

Oil accounts for approximately 99% of Iraq's exports, 85% of the state budget, and 42% of its GDP. While oil has long been a critical pillar of Iraq’s economy, the decades following the 2003 war were especially pivotal in entrenching the country in the rentier economic model it now struggles to diversify away from.

In 2023, Iraq exported approximately 3.467 million barrels per day (mbpd) of crude oil, ranking as the world's fourth-largest oil exporter that year. However, despite this seemingly positive outlook, this figure represents a decline from the previous year, when Iraq exported 3.712 mbpd. Current export rates remain below the peak achieved in 2019, when the country exported 3.968 mbpd.

Thus far, the losses from reduced exports have been offset by persistently elevated oil prices driven by conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza. This has allowed the Iraqi economy to remain on a growth path, with experts predicting that higher oil prices will continue in the near term, placing Iraq's finances in a favorable position. However, while oil prices may remain high, demand could soften; for instance, any slowdown in China's demand for oil could potentially diminish Iraq's gains from elevated oil prices over the past few years

While Iraqi oil production is not directly threatened by militant or terrorist groups, the sector still faces indirect security risks from their activities. Following the shutdown of the KRG-managed oilfields in the north due to a dispute over exports, much of the country's oil production shifted south to Basra Province. While regional demographics suggest IRI-linked groups and fighters are likely heavily present in southern regions of Iraq, these groups have little interest or motivation to directly attack Iraqi oil production. However, the region continues to experience militia rivalries that often escalate into open conflict. In 2022, Basra saw widespread clashes between rival militia factions, exacerbated by the political situation at the time.

Although these clashes have not yet forced the closure of any oil terminals, this remains a possibility in the future, particularly given the aforementioned allegations of some local militias' involvement in oil smuggling. If terminal closures were to occur, Iraq could face substantial losses in oil revenue, similar to the situation in Libya. Libya has experienced frequent militia infighting around the oil crescent, forcing recurring—and costly—closures of oil terminals, such as a mere three-day spate in 2024 which cost the country an astounding $120 million in profits.

Iraq's electricity grid is also a source of vulnerability. Chronic power shortages have forced the country to rely on Iran for electricity, underscoring Baghdad’s need to expand into alternative and sustainable energy sources. To that end, in February 2024, Iraq’s National Investment Commission announced plans to deploy approximately 12 GW of solar capacity by the end of 2030, as well as explore options for waste-to-energy projects and wind energy. Additionally, the French energy firm TotalEnergies also announced it would complete the first phase of a solar power plant and an initial gas project in Iraq by 2025, attributing renewed momentum for these and other previously delayed projects to improved stability in the country.

However, these projects could become tempting soft targets for groups like IS, which has already targeted vulnerable spots in Iraq's power grid during its insurgency. Such initiatives also face challenges due to a lack of clear legislation and the poor state of transmission networks. Furthermore, despite the Iraqi Central Bank allocating approximately $750 million in low-interest loans to help individuals and companies switch to solar energy, uptake has been slow. Thus, while Iraq's energy sector is showing positive progress, reliance on oil and tenuous national stability continue to pose risks to its sustained development.

The Construction Sector

Another sector that has benefited from the ongoing upward trend in Iraqi stability is the construction sector, which has witnessed immense growth following the resumption of economic activity after the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023, the Iraqi construction market amounted to $10.7 billion, with an expected average growth rate of 4% annually between 2025 and 2028. Much of the sector’s growth is expected to be driven by public and private sector investments into transportation, renewable energy, and housing infrastructure. In this context, the lion’s share of total construction investment has been in residential construction, followed by commercial, industrial and energy infrastructure.

Notably, significant investment flows into Iraq’s construction sector come from Gulf States which are tentatively improving ties with Iraq after years of chilly relations. Looking to draw Iraq away from Iran’s orbit, Gulf financial institutions such as the Saudi Public Investment Fund pledged around $4 Billion for mixed-use projects including offices, shops, and over 6,000 residential units across the country. Qatar and the UAE have made similar pledges.

Outside the Gulf, China has emerged as a major source of investment in Iraq. In 2021, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) offered $45.6 billion in financing for construction projects globally, with Iraq emerging as the strongest destination for Chinese investments—$10.5 billion—even as BRI investments floundered elsewhere. Financed projects include the construction of a new heavy oil power plant in al-Khairat (near Karbala), as well as homes and schools. These projects are financed via oil exports, in line with China’s BRI development model.

In addition to general construction projects, Iraq is investing in megaprojects to bolster its infrastructure and capitalize on its favorable location in the Middle East. The most ambitious of these endeavors is the Development Road, a $17 billion project agreed upon by Iraq, Türkiye, Qatar, and the UAE. This project foresees the development of the Al-Faw Port in Basra to accommodate increased capacity, which will then be connected to the Turkish border via road and rail links. Upon completion, the Development Road is expected to offer a 10-day advantage over shipping via the Suez Canal. Furthermore, this new route provides a viable alternative to the U.S.-backed India-Middle East-Europe Corridor, which has become politically untenable since the conflict in Gaza erupted.

On the political front, Baghdad has made significant efforts to secure buy-in from countries not initially involved in the project. In addition to efforts to gain Iran's support, Iraq has discussed linking the Development Road to BRI, thereby avoiding alienating China—considered by some analysts as a potential loser in the Development Road proposal.

Benefits and buy-in aside, Iraq’s construction sector continues to face a number of challenges that can hamper the viability of such ambitious projects. The first and foremost concern is the fact that the sector is heavily influenced by government spending, so public, government, and political dynamics have a strong influence on its development. As Iraq remains heavily reliant on oil, the knock-on effects of any oil shock could very feasibly cause these projects to fail. This is a major concern within the context of both China as an oil-importing state with slowing demand, and Gulf investors who (as oil exporters themselves) would be similarly vulnerable to price shocks. Indeed, the case of Angola should prove instructive: the country engaged in large-scale construction projects bolstered by oil sales to China, only to find itself struggling to finance its debts as Chinese demand dried up.

Finally, inefficiency and corruption within the Iraqi state are ongoing concerns. The country has a history of announcing ambitious infrastructure megaprojects during periods of stability, only for these projects to flounder due to inefficiency, corruption, lack of capacity, or renewed conflict. Meanwhile, Iraq has failed to implement even modest projects that could significantly improve local and urban infrastructure.

The Development Road: A Convergence of Risk Factors

The Development Road is a high-reward project representing the most ambitious initiative Iraq has undertaken in its post-war history. It holds the potential to reshape the Iraqi economy and reduce the country's near-exclusive dependence on oil exports. The construction and maintenance of the Development Road alone are expected to create thousands of jobs for Iraq's young and underemployed population. However, the project also exemplifies a convergence of security, economic, and political risk factors that could impact its long-term potential, as well as Iraqi reconstruction and stability more broadly.

Security Risks

The Development Road, if completed, will run the length of Iraq, from Basra’s al-Faw Port in the south to the Turkish border in the north. While it is presently unclear if the Development Road will run through the KRI, or exclusively through the areas under Baghdad’s direct control, the fact remains that it will pass through the parts of Iraq with the highest levels of insurgent activity.

IS and the PKK represent the greatest security threats to the Development Road, deploying tactics driven by different motivations but potentially leading to the same disruptive outcomes. For IS, such actions align with their modus operandi of attacking trade routes or extorting them for financial gain. During the 2010s, the group frequently waylaid truckers operating between Baghdad and Amman. While truckers were sometimes punished or executed under accusations of carrying illicit items such as alcohol and tobacco, the group was also known to extort levies ranging from $300 to $1,000 for safe passage, which were used to finance their broader mission. There is a very real risk of IS employing the same strategy against trade routes established between Basra and Türkiye as part of the Development Road, significantly reducing the project's commercial viability. Moreover, the Development Road could provide ample opportunities for increased ransom, extortion, and looting to finance IS activities, thereby amplifying the threat of terrorism across the country.

A similar risk exists with regards to the PKK: although not primarily known for such tactics, the PKK has sporadically conducted attacks on convoys and other targets along trade routes, particularly in Türkiye. More significantly, the group continues to launch attacks against Turkish security forces near the Turkish-Iraqi border. Although the number and intensity of these attacks have declined in recent years, the region still experiences frequent security incidents. Beyond attacking soft targets, the PKK could intensify its attacks on Turkish military bases in the region, potentially resulting in a costly war of attrition that would render Türkiye's economic goals increasingly unviable. Although Turkish operations against the PKK in northern Iraq appear relatively successful, the prospects for long-term and sustained security remain unclear. In this context, the PKK has both the motives and opportunities to make the Development Road as costly as possible for Ankara and Baghdad.

Thus, far from ensuring Iraqi reconstruction, the Development Road could facilitate a resurgence of terrorism, further undermining Baghdad’s credibility, both international and domestic, as a guarantor of Iraqi national security. This, in conjunction with economic losses incurred from the attacks, could cause the Development Road to rapidly lose its viability before it has a chance to offset its costs, rendering it an expensive failure.

The IRI, meanwhile, is unlikely to threaten the Development Road directly, though its attempts to interfere in the investment and construction of al-Faw Port sets a disturbing precedent for the project’s future. Given the close links between these groups and Iran, and the growing Iranian dominance in Iraqi politics as a whole, the IRI and similar groups may find themselves able to operate without contest, intimidating businesses into favorable terms and strong-arming undesirable investors out—to the detriment of the Development Road and Iraq as a whole.

More significantly, the presence of Iran-backed groups in the region, combined with the port's proximity to Iran, could make it an attractive target for external military operations by countries like Israel. Israel has a history of conducting strikes from Syria to Yemen targeting Iranian-backed proxies. For many investors, the risk of getting caught in such crossfire may outweigh the potential benefits of the Development Road. Additionally, the possibility of business entanglement with Iran-backed entities could be particularly unwelcome for Gulf investors, even amidst the ongoing détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Economic and Political Risks

Economically and politically, the Development Road risks failing for the same reasons other megaprojects in Iraq have failed. The country has a history of announcing grand projects with much fanfare, only for them to collapse due to a mix of corruption, mismanagement, and fluctuating financial fortunes. Although Iraq has undertaken legal and structural reforms to raise investor confidence and has engaged in diplomatic efforts with stakeholder countries to facilitate the success of its endeavors, success is far from guaranteed.

Foremost among investor concerns is the Iraqi economy’s reliance on oil and its resulting vulnerability to price shocks. As discussed above, the construction sector is heavily influenced by state income, which is dependent on oil revenues. Although projections suggest steady GDP growth for the next few years, these forecasts do not account for unpredictable price shocks or supply bottlenecks resulting from external military action or worsening domestic security conditions. Over the short term, today's fluid geopolitical and geoeconomic environment mean sustained stability will likely remain out of reach.

This risk extends to the Development Road's other investors as well. Qatar and the UAE are also hydrocarbon-reliant states, and despite both having made significant strides toward diversifying their economies—far more so than Iraq—they remain similarly vulnerable to external shocks. The 2020 oil price crash is a strong example; although Qatar and the UAE weathered the crisis better than Iraq, their economies still suffered deficits. A repeat of such conditions could lead these countries to downgrade their investments, potentially causing the Development Road to downsize or even be canceled. Moreover, Saudi Arabia's quiet scaling back of ambitious flagship megaprojects like NEOM bodes ill for other projects of similar scale in the region.

Politically, Iraq remains fractured and prone to decision paralysis and deadlocks. The ruling Coordination Framework under Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani is closely aligned with Iran, and has therefore managed to establish a semblance of coherence among the various pro-Iran factions. However, this alignment is far from popular among a significant portion of the Iraqi populace, as well as Iraqi nationalists, who favor Baghdad's disengagement from Iran. Tensions between these groups—which transcend the country's typically sectarian politics—brought Iraq to the brink of civil war in 2022.

Thus, political conditions in the country remain a significant source of risk and could easily propel it into a new period of instability, paralysis, and rapid government transitions. These political developments contribute to risks that could delay or derail the Development Road project, spooking investors and reducing confidence in Baghdad's ability to maintain a business-friendly environment.

Conclusion

CENTCOM's July assessment of the IS resurgence in Iraq and Syria is significant, and Iraq faces numerous challenges that could undermine its long-term stability. In this context, the Development Road megaproject serves as a case study of these converging risks. Despite its potential to drive economic diversification and reconstruction, the project exposes Iraq to significant political, economic, and security vulnerabilities. Insurgent threats from IS and the PKK, coupled with political fragmentation, corruption, and dependence on oil revenue, create numerous potential points of failure. If these issues remain unresolved, Iraq's fragile recovery could falter, providing the very conditions under which IS could re-emerge and further destabilize the country. Ultimately, Iraq's ability to manage these risks will determine whether it can truly move toward stability or remain vulnerable to renewed conflict and insurgency.