+ Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia provided over 40% of Europe’s gas. Import numbers have steadily declined to about 8% as of 2023 per official figures.

+ European leadership is in search of alternative energy routes that reduce reliance on Russian energy, aligning themselves with the US strategic outlook for the region.

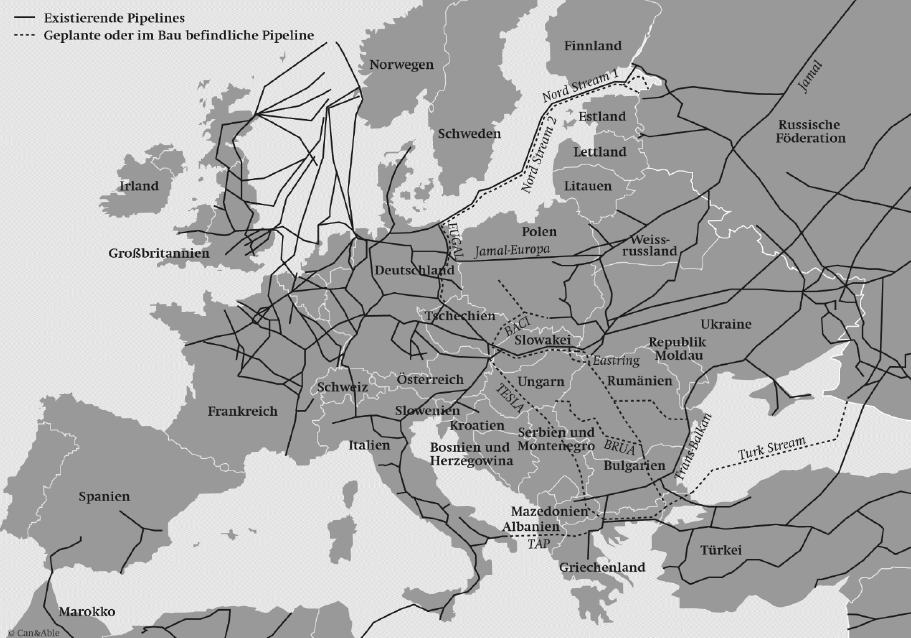

+ Norway, North Africa, TurkStream and Trans-Caspian pipelines promise potential solutions for the future, but most suffer from geopolitical risks and investment hurdles.

+ Connecting Israel and Cyprus gas fields to the European mainland gains urgency, leading to renewed diplomatic efforts to create energy security and co-operation in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The 2022 Nord Stream pipeline explosions served as a wake-up call for many in Europe, and came at a critical moment in European history. During the Cold War, dominating energy infrastructure and supply across the USSR and its satellites was a powerful means of exerting Moscow’s control within and across borders. Power over energy supply means control over economic trends, all types of industry, whether people can heat their homes and cook meals, whether hospitals function, and even whether a nation can physically provide for its own national security. Today, we see this lever of Soviet—now Russian—influence still effective in Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. While diversifying energy away from Russia and Russian-controlled infrastructure and transport will take time, it’s never been more widely supported in Europe.

In exploring alternative gas supplies for Europe, the Eastern Mediterranean emerges as a critical yet under-appreciated region. Recent discoveries have confirmed significant natural gas fields that are geographically well-placed to meet Europe’s evolving energy needs. This development offers a valuable opportunity for nations, the investment community, businesses, and local communities alike—providing a new option to address the demand signals and realities of the European energy market post-2022.

Nord Stream Blows Up

A quick look back at how Nord Stream became a symbol of Europe’s unfortunate dependency on Russian energy helps inform a path back to energy diversification—and ultimately, energy security—in Europe.

All Nord Stream pipelines begin on the Russian mainland, crossing the Gulf of Finland and extending westwards through the Baltic Sea to terminate in Germany. These pipelines traverse the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of several countries, including Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. In September 2022, Danish and Swedish seismologists detected a blast on the floor of the Baltic Sea, equal to 1,100 pounds of TNT, just east of Bornholm. Danish F-16 jets patrolling in the area spotted the massive gas leak on the surface. The leaks originated from three out of four segments of pipeline within the Danish EEZ. In response, Denmark, Sweden, and Germany immediately opened investigations into the incident. While the German investigation is still ongoing, Danish and Swedish authorities have concluded their investigations without naming a responsible party. Though the pipelines were not operational at the time of the explosion, they were pressurized with methane. Record amounts of methane have since leaked into the atmosphere, marking the world’s largest leak of this kind, and creating a catastrophic ecological disaster.

The sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines prompted a major reassessment of energy security strategies among European leaders. At the time of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Germany, Europe's leading economy and EU powerhouse, was significantly reliant on Russian gas imports. This became a central pain point after the Russian invasion, as the German government drew criticism for its cautious stance toward support for Ukraine. Critics argued that Germany's hesitancy to provide full support to Ukraine stemmed from its dependence on Russian energy.

As war unfolded in Europe at a scale not seen since Wold War 2, it became clear to most European leaders that Moscow could no longer be trusted in any meaningful sense. This realization compelled European nations to urgently seek alternative energy sources, marking a significant shift in the continent’s energy policy landscape.

Searching for a New Normal (for European Energy)

As Europe sought alternatives to Russian gas, a diverse yet developing array of options emerged. The United States, eager to reduce Russian influence over Europe, stepped in with increased LNG exports. Closer to home, Norway and North Africa emerged as promising sources of gas to meet the continent's new demand. Norwegian exports in particular surged over 2023, with a 250% increase in the first half of that year. Nevertheless, this was not sufficient to fully offset the shortfall created by the pivot away from Russian gas. In contrast, North Africa, despite the region’s potential to produce large quantities of gas, faces its own set of challenges; substantial investments and modernization efforts would be required to actually bring those higher export volumes to market. Algeria is a prime example, as it is hindered by domestic political and bureaucratic hurdles that would need to be overcome before it could become a trusted player in Europe's energy diversification push.

Looking East, despite the risk of falling under Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions (CAATSA), TurkStream continues to deliver Russian gas to Eastern Europe through the Black Sea. However, outside of geopolitical tensions, this also means specialized Western equipment is required for essential maintenance operations, which raises further questions about the longevity and reliability of this energy route. Similarly, the Trans-Caspian Pipeline, which proposes a gas route from Central Asia through Azerbaijan and Türkiye, suffers from significant potential risk, due to the region’s exposure to the spectrum of Russian interference. The proposed route for the first leg is an undersea link through the Caspian Sea, a closed body of water where Russian interests operate virtually unchecked. This route, while at first seemingly viable, is effectively “dead in the water”: Russia has an established history of opposing this pipeline, halting development plans during previous efforts. A future Trans-Caspian Pipeline is likely to face similar geopolitical challenges.

The Eastern Mediterranean Option

Recognizing these challenges, European and American stakeholders turned their attention to a burgeoning opportunity in the Eastern Mediterranean. The region's energy landscape began to transform dramatically in the 2010s with the discovery of substantial gas fields off the coast of Israel. These new discoveries, most notably the Leviathan gas field, revealed the energy potential of the Eastern Mediterranean region.

Not long after these discoveries, Cyprus began its own exploration within its Exclusive Economic Zone, awarding contracts to global energy corporations like Shell, Exxon, and Eni. This initiative sparked a wave of ambitious projects aimed at leveraging these resources, including plans to transport gas to Europe. Prominent among these was the EastMed Pipeline which proposed a route via subsea pipeline connecting Cyprus directly to Greece and Italy, highlighting the strategic importance of the Eastern Mediterranean as a potential energy corridor to Europe.

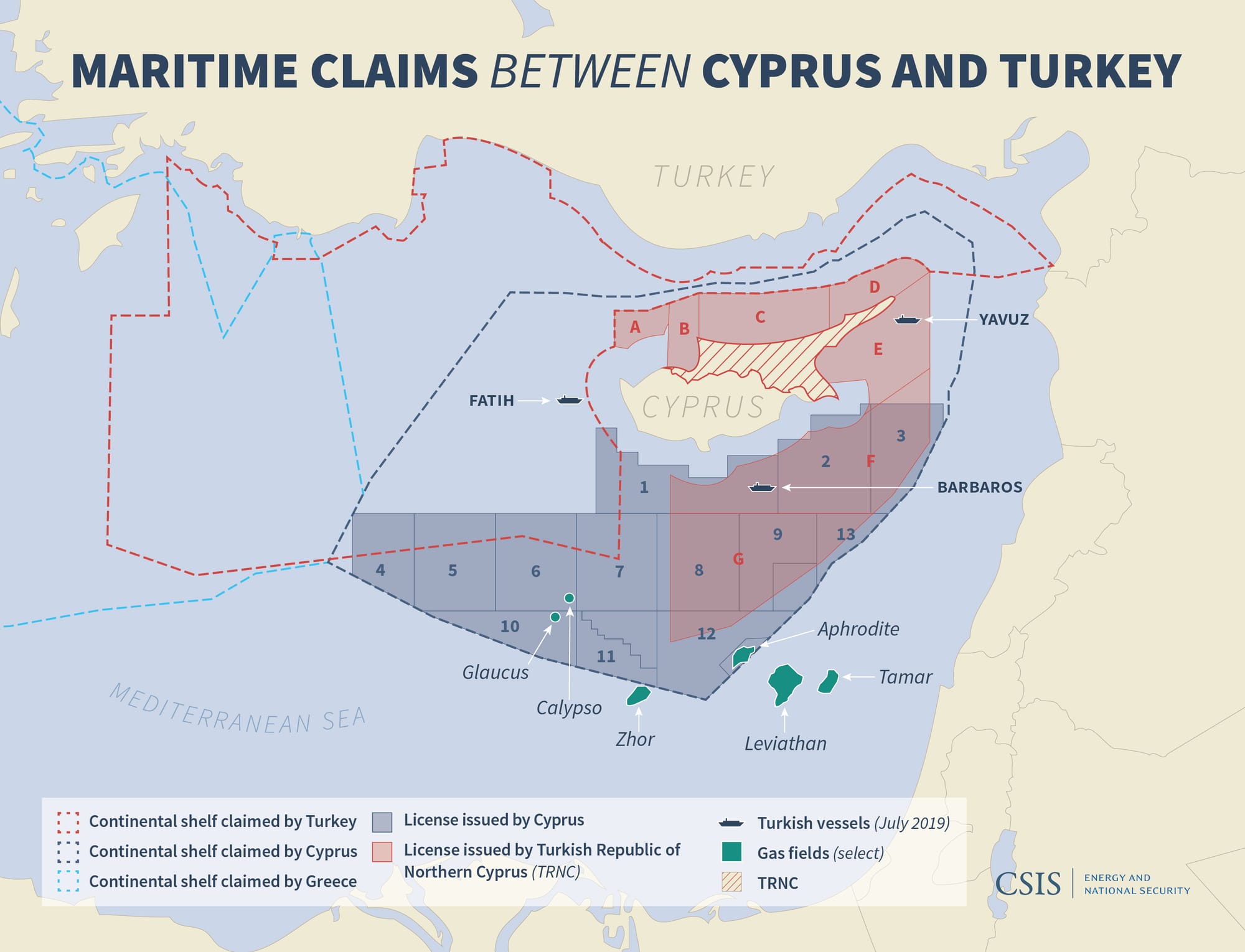

It was at this point, however, that the complex political history of Cyprus began to complicate the development of the newly discovered gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean. The island has been divided since the 1974 Turkish military intervention, which followed decades of intercommunal violence and displacement among Turkish and Greek Cypriots. This led to the establishment of a de facto Turkish Cypriot state, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) in the north, declared by the ethnic Turkish minority, while the Greek Cypriots maintained control of the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus in the south. Despite its ongoing division, Cyprus stands at the center of a critical yet complex opportunity, potentially serving as a linchpin in securing a stable and reliable gas supply to Europe.

As a military and economic power in the region, Ankara wields significant influence over gas exploration and development efforts in the Eastern Mediterranean, including sending naval assets to challenge exploration efforts in areas contested by Türkiye. As the internationally recognized entity on the island, the Republic of Cyprus lays claim to the hydrocarbon resources off the coast of Cyprus. However, the facts on the ground complicate these assertions in practice. Türkiye's stance is partly rooted in the claims of Turkish Cypriots in the TRNC. As an internationally exiled community, Turkish Cypriots must rely on Türkiye for a number of functions of state, including the protection of TRNC maritime interests.

An additional basis for Ankara's contested claims is rooted in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Despite that Türkiye is not an official signatory of UNCLOS, like the US, it enforces and abides by it. UNCLOS stipulates that in cases of overlapping maritime interests, the involved parties are required to negotiate and sign an agreement to delineate maritime boundaries. The longstanding historical conflict and the recurring diplomatic gridlock between the parties involved have made it clear that achieving a functional maritime agreement to realize a critical new gas supply to Europe is not possible without first resolving the "Cyprus problem.”

Thus, reflecting the interests of both Turkey and the Turkish Cypriot community, the Republic of Turkey has asserted claims that challenge those of the Republic of Cyprus. While the rest of Europe watched, Turkish drilling ships protected by naval and drone assets began counter exploration efforts on the seafloor. The Turkish show of force effectively halted any Republic of Cyprus momentum towards developing its energy projects. Furthermore, Turkey entered into a maritime deal with Libya's UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA). This agreement cuts through the planned route for the EastMed Pipeline, effectively attempting to scuttle it, and drawing immediate criticism from Cyprus, Israel, Egypt, and Greece.

A Potential Lightning Round: Investment Could be Unlocked Overnight

The energy problem centered around Cyprus in the Eastern Mediterranean should be on every Middle East-focused investor’s watchlist. Resolving this political blockade could open the region on a scale not seen in the modern globalized era. The region has been in political gridlock since the early 1960s, meaning that parties have been politically entrenched and isolated since before the information age. Currently, goods and services cannot move directly between Turkish and Republic of Cyprus ports due to this political deadlock, which also complicates the energy issue in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Turkish and Cypriot companies have been raising the issue of market access with the UN for years and preparing for it.

In the event of a solution to the gridlock, we anticipate a rapid and immediate unblocking of the logjam, presenting significant opportunities for businesses due to newly accessible ports and trade agreements. Israel, Egypt, Greece, Lebanon, and other states in the region will be able to dock at ports in North Cyprus. Turkish shipping and goods will have access to Republic of Cyprus ports, and the Republic of Cyprus will gain access to Turkey’s large market for the first time in over half a century.

This new and streamlined trade in the region will open fresh links between countries and reintegrate economic ties. Turkish and Cypriot companies have been raising the issue of market access with the UN for years and preparing for it. Isolated North Cyprus will attract investment from the international community, and the Republic of Cyprus will be able to tap into Turkish industrial might.

A New Envoy, a New Hope

The energy crisis created by Russia’s war in Europe has reignited initiatives to resolve the Cyprus problem, and the concomitant impasse regarding energy development. January 2024 marked a new hope for the region with the appointment of Maria Angela Holguin as the new UN envoy to Cyprus, signaling renewed efforts to address the longstanding conflict. Chatter in diplomatic circles indicates a growing dissatisfaction with the longstanding impasse. By advocating for a solution to the half-century old frozen conflict on Cyprus, the international community is demonstrating that stability in the region has become an urgent priority.

Just as Alexander the Great was confronted with an intractable knot that none before him could untie, Holguin faces a similarly daunting challenge in the Eastern Mediterranean. This knot, however, is made up of decades of division, diplomatic standstills, and intertwined yet competing interests.

To be clear, she will face headwinds. Decades of division and years of diplomatic stagnation make Holguin’s mission challenging. Nevertheless, the potential rewards of her success could be seismic for the region, but also for Europe’s energy security. Further, the frozen Cyprus conflict is also a thorn in the side of EU-Turkish relations. Resolving it could pave the way for Israeli and Cypriot gas to be efficiently integrated with the existing Turkish pipeline network that extends to Europe. This would not only expedite the realization of the EastMed’s goal to meet lucrative demand in Europe by reducing costs and shortening timelines, but it would also bolster regional cooperation—and attract increased investment.

Today, the hope of disentangling the numerous longstanding issues and personalities in the region now lies with Holguin and the UN. The resolution of the Cyprus conflict, and by extension, securing Europe's energy future, presents Holguin with her own diplomatic Gordian Knot. Just as Alexander the Great was confronted with an intractable knot that none before him could untie, Holguin faces a similarly daunting challenge in the Eastern Mediterranean. This knot, however, is made up of decades of division, diplomatic standstills, and intertwined yet competing interests. The hope remains that Holguin, like Alexander, can find a decisive and lasting solution to cut through the entanglements. Achieving this would not only untie the knot of the Cyprus problem but also unlock a pathway to greater energy cooperation, economic growth, and security in Europe as well as the Eastern Mediterranean.