+ Rising global demand for minerals, driven by geopolitical competition to secure sovereign supply chains for the green revolution, finds promising prospects in the geophysically advantageous Arctic, made more accessible by climate change.

+ The Arctic Ocean, Earth's shallowest at 1,204 meters compared to the deepest Pacific's 4,000, offers greater operational ease for deep sea mining, making it more cost effective than mining in other depths and on land. Adding to the appeal are hydrothermal vents abundant in diverse ores and rare earths, with deposits providing up to 99% usable material, versus 20% from land sources.

+ Most of the Arctic seabed falls under sovereign jurisdiction or awaits UN arbitration, offering mining companies the possibility of favorable tax and policy treatments within boundaries as states compete to attract investment and boost their economic and national security imperatives.

+ In contrast, the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which governs much of the Pacific seabed, has a complex political landscape, often slowing down regulatory processes and mining operations as a result of its consensus-based organization that must balance often conflictual member state priorities.

The Arctic, long known for its substantial proven reserves of oil and natural gas, is also home to large quantities of critical minerals necessary to help alleviate growing demand over the coming decades. Access to sovereign supplies of these minerals, including rare earths, is driving new geopolitical competition and commercial opportunity. Consequently, the Arctic, including its transnational areas, is an increasingly attractive option for deep sea mining exploration and exploitation. Investment is likely to continue rising due primarily to a warming climate, newfound accessibility, and regional interest. The appeal of offshore mining in the Arctic lies not only in its reserves of critical resources, but also in the distinctive geophysical characteristics that differentiate it from other seabed and land-based alternatives. Furthermore, the national regulatory frameworks that currently apply to deep sea mining in the Arctic can be more conducive to resource development than other offshore regions.

Going Low to go High: Shallowness and Higher Quality

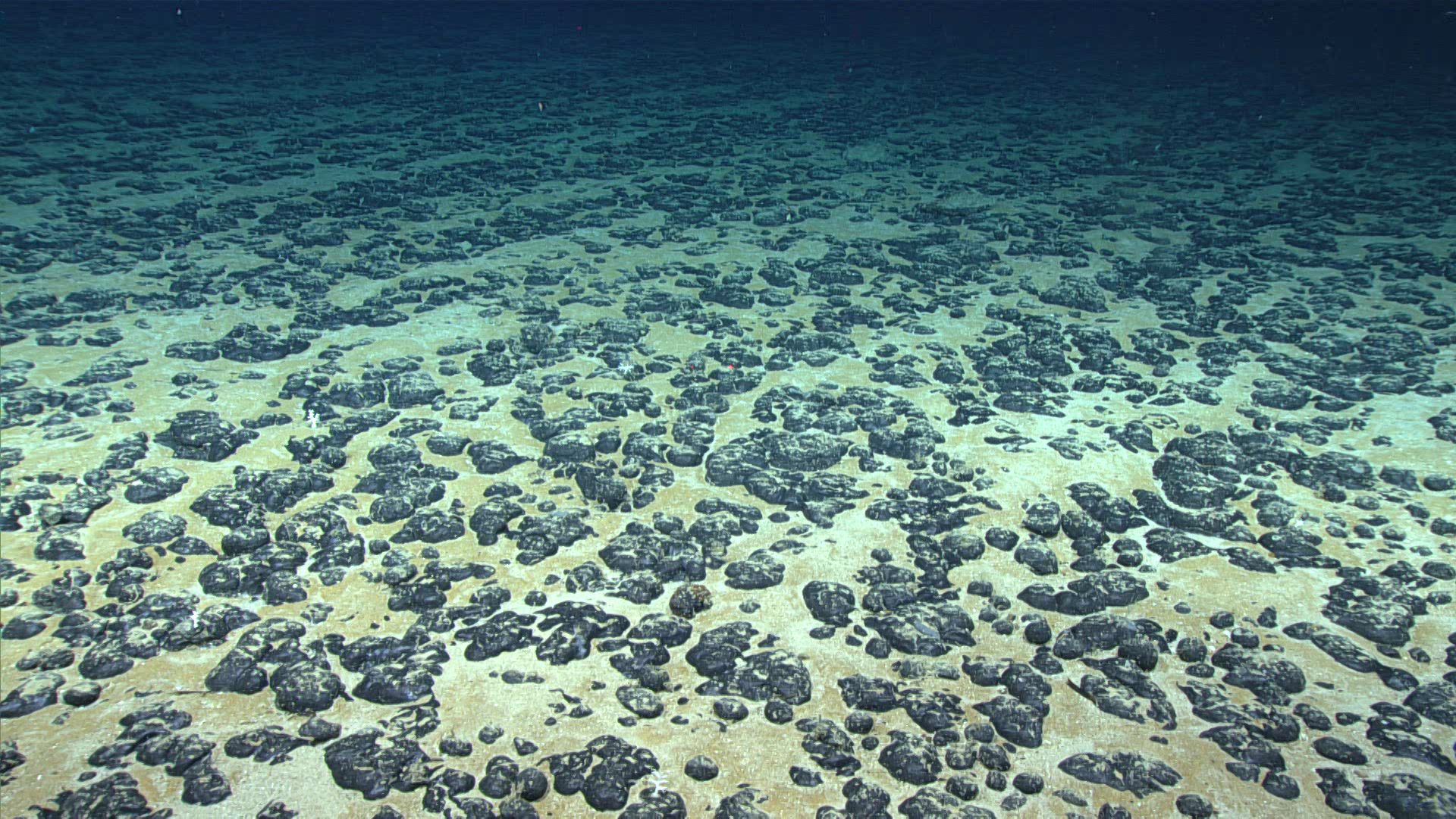

Fundamentally, the Arctic Ocean’s shallowness is a significant comparative advantage. The Arctic Ocean is the shallowest of Earth's five oceans with an average depth of 1,204 meters. This is substantially less than the 4,000-meter average depth of the Pacific Ocean, currently the global hub of deep sea mining activity and home to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, where much of the activity is concentrated. Historically, the issue of cost-effectiveness at varying ocean depths was a significant contributing factor to halting the industry in the 1980s. Mineral prices had been inflated prior to 1974, and subsequently began a steep decline as more efficient resource utilization in land-mining became widespread, and a wider global slowdown in productivity exacerbated this price trend. The depth of the mining site has a positive correlation with the operational complexity, logistical cost, and associated risks, making the Arctic's relatively shallow depth an undeniable advantage.

Today, the growing global decline in ore quality from critical land-based mines is leading to increased extraction and processing costs, with a significant impact on future profitability.

The unique geography of the Arctic Ocean provides another critical benefit, even compared to Arctic land-based mining: the Arctic Ocean has a significant number of hydrothermal vents. These are vents where concentrations of minerals such as copper, gold, and zinc are usually found in significant quantities. Today, the growing global decline in ore quality from critical land-based mines is leading to increased extraction and processing costs, with a significant impact on future profitability. This trend among land-based mines coincides with the potential for the Arctic's deep sea mining to harvest a variety of both ore types as well as rare earth elements from a single site. Given the consistently higher grades of seabed-mined ores, deep sea mining could prove notably more cost-effective, especially when considering it requires far less by way of infrastructure and transport systems than terrestrial mining. Further, seabed deposits have the potential to provide substantially more usable material: on average, 99% of a seabed deposit is potentially usable material, compared to just 20% from land-based sources. This efficiency underlines the strategic importance of the Arctic for future deep sea mining operations, and explains why Arctic and non-Arctic nations alike are backing companies to compete for these resources in the High North.

Stabilizing Political Risk Factors

There are key regulatory features involved in Arctic deep sea mining that can have outsized effects on commercial development. For example, as nearly all the seabed in the Arctic is currently administered or claimed by a sovereign state, with submissions pending with the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) to arbitrate most remaining areas, nearly all deep sea mining sites will eventually be under a sovereign national jurisdiction. This potentially means plentiful opportunity for seabed mining companies to seek preferential treatment, playing on economic competition between states and taking advantage of far more dynamic or favorable tax and policy regimes. None of that, however, is possible for operations that fall within the international seabed, and so are beholden to the International Seabed Authority (ISA) as most Pacific seabed mining will be.

Nauru also emphasizes deep sea mining’s role in their climate change adaptation plans, specifically as a means to promote green technologies that might help prevent the expected loss of the island to rising sea levels.

The ISA’s eventual regime has far more political caveats to consider, including required agreements shared across all signatory nations, who often joined with competing agendas. For instance, Canada joined hoping to protect the competitiveness of its domestic nickel mines, while Fiji is keen to place environmental protection concerns front and center. The latter’s efforts to slow ISA deep sea mining development run up against states like Nauru who are pushing for its acceleration in light of its perceived economic advantages. Notably, Nauru also emphasizes deep sea mining’s role in their climate change adaptation plans, specifically as a means to promote green technologies that might help prevent the expected loss of the island to rising sea levels. The ISA’s political landscape is further complicated by its own leadership being accused by key signatory members of bias and overstepping its authority, for pushing to accelerate the start of deep sea mining while resisting measures by conservationist-focused members to slow down the process.

This all leads the ISA's framework to be less dynamic, and its political risks more complicated, than its national counterparts can potentially be. This is because it has to take into account a diverse, and often oppositional, range of aims from its members within a system that requires all 36 voting members to be in consensus for regulations to be approved. The ISA also has historically been incredibly slow to regulate and facilitate deep sea mining. In fact, it only started on a framework for exploitation in 2021 when Nauru gave notification that it intends to start deep sea mining, triggering the “2-year rule” and forcing action. The reason for the ISA’s delay is due to the diametrically opposed tasks it performs: to both protect common seabed environments from harmful activity, while also developing a seabed resource exploitation framework which distributes profits. This means in practice that license applications could be slow to progress compared to national regimes that are not beholden to the ISA, like Norway in the Arctic, which is already considering commercial licensing this year and opening up large areas of its seabed to such activity.

Price Security and Long-Term Profitability

These points together mean that as climate change melts the sea ice, the Arctic will be a source of increasingly significant interest for deep sea mining, with lower cost, more favorable long-term conditions, and a likely more beneficial regulatory framework than the ISA can offer in other deep sea jurisdictions. Alongside the wider context of increasing mineral demand to fuel the green revolution and technologies designed to combat climate change, this will see Arctic seabed mining have a far larger buffer to any 1980s-style price and demand trends.

Today, the trend in mineral prices has seen consistent upward movement, and momentum is only set to grow as global demand both real and expected continues to rise. Global geopolitical competition over sovereign supply chains for the materials essential to modern technologies, and that fuel the green revolution more broadly, are driving the trend. Such competition in this space has led directly to increased investment flows that benefit commercial activity in the region. In this context, the shallower Arctic, abundance of thermal vents, and dense nodules of high quality ores and rare earths present a greater degree of price security for deep sea mining stakeholders. Even if critical mineral prices begin to plateau as new sources are found in the coming decades, operating costs in the High North should continue to decline as accessibility increases and infrastructure spreads northward. These larger trends should continue to protect the longer-term profitability of Arctic deep sea mining compared to land-based mining, as well as offshore mining in other geographic regions.